Ghost Story

By Arne Brogger

Business took me to Nashville for three days and I decided to take a long weekend and visit Memphis. I hadn’t been there in almost twenty years, not since the funeral of my old friend and co-conspirator, Walter “Furry” Lewis. Furry was a charter member of the Memphis Blues Caravan (MBC), a group of geriatric bluesmen whom I had the pleasure of booking and managing in the Seventies.

On a Friday morning I headed southwest out of Nashville on I-40 (The Music Highway, as the sign said) across the Tennessee River, through the rolling Cumberlands, on down to the brown and wide Mississippi. I had promised myself this trip for years. I had fantasized about it. Obsessed over it. It was like a reverse Vision Quest. I wanted to go back, to recapture scenes that had been an important part of my life, but knowing all the while that was not possible. Most of the folks I had known were now gone. But they had stayed with me – and I thought…who knows what I thought. I knew it was a trip I had to take.

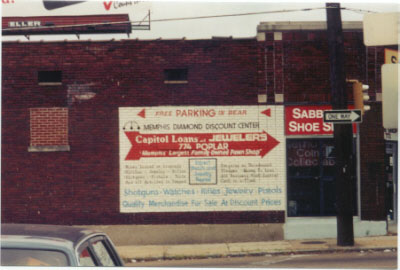

Capitol Loans

I arrived early afternoon. The first stop was the Cozy Corner Café, BBQ ribs and chicken (with a side of beans), just to get in the right frame of mind. Then up Poplar Avenue to the intersection of Mannassas, where sat the global headquarters of Capitol Loans. Capitol was the pawnshop where Furry would hock his guitar every time he came off the road. When it was time to go back out again, it was up to me to “un-hock” it so that he could play the dates.

Turning on Mannassas I drove one short block to Mosby Street where Furry had once lived at number 811. The house is gone, having burned down a month before he died of complications from the fire. But standing next door was its duplicate. A four-room shotgun style house. Six or eight folks were sitting on the front porch. I asked if any of them knew Furry Lewis who used to live next door. An old woman volunteered, “the gittar picker?” I nodded. “You know he gone. Passed some time ago.” Yes, I know.

I looked over at the empty lot and remembered walking up on the porch, through the front door, into main room where Furry sat on his bed. A whiskey glass stood on the table next to him covered by a saucer. “Spiders” he said, “can’t see too good. Don’t want no surprises.” That was in 1973.

Big Daddy’s Office

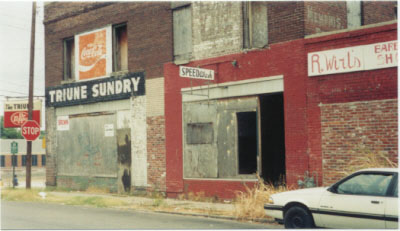

Bukka White’s “office” consisted of a chair leaned against a brick wall. Next to the chair was a wooden crate. Both sat on the shady side of the street beside Triune Sundry. This is where I first met him, having been told earlier by his wife that “Big Daddy ain’t home. He’s at his office.” Cruising the streets near Mosby, I knew it was around the area somewhere. Suddenly something told me to turn right at the corner of Leath. There it was.

Triune Sundry

Triune Sundry

It was a hot day in 1973 when I had first stood on that corner and shook hands with a legend. He was B. B. King’s big cousin and had given B. B. his first guitar, a Stella. Muddy Waters would later tell me that there were licks Bukka did that he (Muddy) was still trying to figure out. And Bukka was the man who literally sang his way out of Parchman Farm Prison. I stood on the corner for a while. I took a few pictures. I could hear the rolling thunder of Aberdeen Blues and see his hands, hopping back on forth on the guitar. I got in the car and headed for Beale.

Daddy’s Dogma

At the back of 333 Beale Street is the photo studio of Dr. Ernest Withers (an honorary degree from Memphis State University). He’s an ex-Memphis cop, one of nine who were the first black cops in town, circa 1946. The studio consists of two rooms; each piled high with stacks and stacks of photos, in no particular order. There wasn’t a camera in sight. I was introduced to him by my “tour guide,” Denise Tapp, and I told him that we had a mutual “acquaintance” in Steve LaVere. (LaVere got hold of some Withers negatives years ago and the beef eventually ended up in court.) He told me to take my time and look around. I did. There were pictures of MLK, et al, the whole Memphis civil rights thing, old shots of Beale (like the Review that used to play the Palace Theatre in the Twenties and Thirties), street shots of Beale from 1919, pictures of Johnny Ace driving his “touring car” and shots of every musician of note in Memphis. On the wall over Dr. Withers’ desk stood the following legend:

Sid Selvridge

Daddy’s Dogma

I’ll appeal to your intellect

Then I’ll appeal to your pride,

If that don’t get it,

I’ll get to your hide.

Alfred Earl Withers

1889 – 1969

I stayed two hours.

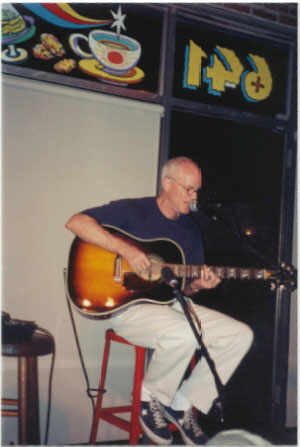

Sid, Mose, Judy, Carol

That evening I saw my old buddy Sid Selvridge play (he’s the producer of the Beale Street Caravan blues show, syndicated on about two-hundred-fifty stations coast to coast). Sid, by the way, played at Furry Lewis’s funeral accompanied by Lee Baker. They rolled the old man out to “When I Lay My Burden Down.” Listening to Sid, I couldn’t believe that this man didn’t have a “deal.” Everything about the guy is perfect – from pitch to picking to presence.

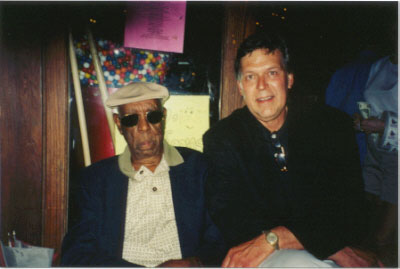

The next night caught Mose Vinson (the last surviving cat who played on the Memphis Blues Caravan) performing at the Center For Southern Folklore. The Center is run by Judy Peiser, a one-woman perpetual motion machine. “Judy, you’re like crabgrass…you’re everywhere.” She laughed. Then she disappeared. Mose is 84 (but claims to be 105) and still plays a mean piano. I told him I always thought he had the best left hand in the business. He smiled…he was trying to remember who I was. I don’t know if it ever got through.

Mose Vinson & Arne Brogger

Listening to Mose, I sat at a table with Carol Baker and one of her three sons. Carol is the widow of Lee Baker, Memphis musical powerhouse and co-founder of such influential bands as Mud Boy & The Neutrons and Moloch. Lee was murdered by two teenaged boys in a botched robbery attempt. The world lost a treasure. I told Lee’s son that I knew his Daddy and that he should be very proud. “I am,” he said, “everyday.”

One Kind Favor…

On Saturday I drove myself down into the Delta, straight down Highway 61. But first I had to pay my respects and headed for the Hollywood Cemetery out by the Freeway. The grave of Furry Lewis lay toward the back. Not knowing exactly where, I looked for some landmark from memory (I had been there once before, when he was laid to rest in 1981). Many of the headstones were hand-carved and the names that stood on them were classic. Lots of Jackson’s and Washington’s, Willie’s and Burtie Mae’s. The ground was uneven, with definite depressions outlining the wooden boxes that had decayed, six feet deeper in the earth. There were few concrete sarcophagi, as found in the white folks’ graveyards. When nature consumed what was left in it, the ground above sank. I parked near the back of the cemetery and slowing walked toward the gate. It had started to rain a bit and my pant legs began to darken as I walked among the graves.

Furry Lewis’ grave

And finally, there it was. Walter “Furry” Lewis, Blues Man. My pal. Wise and funny. A songster and storyteller. I stood there for a while – surrounded by ghosts – reliving an incident that occurred many, many years ago.

Furry was playing a solo date at a college. I was in the dressing room during part of his last set that night. Suddenly, I heard my name being called from the stage. I stumbled out of the dressing room and ran to the lip of the wing. Furry sat with one arm draped across his guitar; he had a gleam in his eye. “Arne,” he said, “seeee that my grave is kept clean.” And then went into the Blind Lemon Jefferson tune. The audience howled.

I placed a small stone on top of the marker. Then I walked back to the car.

61 Highway

Rolling south out of Memphis, down Third Street, the famous US 61 sign suddenly appeared on my right. It was a sign I was very familiar with. I grew up only a few miles from its northern extension. It paralleled the river up from the Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin tri-corner, wound through Minneapolis and then snaked north to the Canadian border some four-hundred miles away. Another fellow Minnesotan, and University of Minnesota attendee, Bob Zimmerman, was equally familiar with this road. It tracked to the east of his hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota (but straight through the city of his birth, Duluth). He would later change his name. And he would write a song about it. Bob Dylan, “Highway 61.”

As I crossed the Mississippi State line, some 20 miles outside downtown Memphis, I began to see billboards advertising various casinos. The frequency of these signs grew as I approach Tunica. At one point, they appeared virtually every fifty yards. Just north of the Tunica Corp. Limit, to my right I could see some of the casinos themselves, peeking above the levee, next to the mile-wide Mississippi.

The River

Dark brown, wider than wide, it was not the river I knew as a kid. Contained by steep banks, the Mississippi flows through Minneapolis and St. Paul; the Twin Cities are situated just above Lock & Dam Number 1. All barge traffic ends about three or four miles upstream from the Lock at St. Anthony Falls. Just below the Falls stands what was left of the docks and buildings that at one time comprised Pillsbury Mill Number One. At the turn of the century, from these docks wheat and flour reaped from the vast Minnesota and Dakota Plains floated south to the railheads of St. Louis. Two blocks from my childhood front door one could put a boat in the water and cruise south, like the huge flour barges of long ago, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Delta

Passing the outskirts of Tunica, the landscape flattened. Cotton fields spread out to the right and left. I was entering the great Mississippi Delta.

Mississippi Delta

The Delta is bordered on the west by the Mississippi River and some 70 miles to the east by the Choctaw Ridge, the beginning of the Mississippi hill country. The Yazoo Delta, as this section is known, sits atop some fifty feet of rich, black soil, deposited by eons of flooding by the Mississippi, before it was contained by the levees. These levees were built at about the same time that the flour, milled fourteen-hundred miles north, shipped off the docks at Pillsbury Mill Number One. Both the flour and the levees were the product of strenuous physical labor – labor that was voluntary and remunerative at the Northern end of the river and completely the opposite at the Southern end.

The vast farms of both western Minnesota and the flat plains of the Dakotas, were peopled largely by Scandinavian and German immigrants. Having sold virtually all they had in order to start a new life, these folks were just beginning to enjoy the rewards and benefits that flowed from hard work and equal opportunity. No one gave them anything – but no one took anything from them either. They spoke English, just barely, and when they did, it was through a heavy accent. They were largely illiterate and could not read or write the language of their new country. But they were among their fellows, their countrymen, some a generation removed from the homeland. The freedom assured by the laws and Constitution their new country allowed them to help and encourage one another and to prosper. And they were all, every one of them, white.

In the levee camps, the workers too, spoke with a heavy accent. They too, were illiterate. But they were not aided or encouraged in their efforts to build better lives, as were their neighbors to the north. And they were all, virtually every one of them, black.

The Black Codes

After the defeat of Reconstruction in the mid-to-late 1800’s, the State of Mississippi was the first to enact a set of laws that became to be known as The Black Code. These were laws which specifically spelled out offences which, when committed by a person of color, could be punished by an equally specific sentence. No distinctions were made as to age or gender. These laws were applied universally across the entire non-white population. Offences ranged from Insolence (as seen in the eye of the beholder) to Theft to Rape and Murder. The latter two, if committed against a member of the white population, were summarily dealt with via a common and accepted practice – lynch law. Cause of death always read the same, “death at the hands of unknown parties.” Every non-white was at constant risk. For more on this subject, read David Oshinsky’s excellent book: Worse Than Slavery–Parchment Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (Free Press Paperbacks/Simon & Shuster, ISBN 0-684-83095-7)

“They worked us like rented mules…”

What the Black Codes accomplished was a reinstitution of slavery via an ingenious phenomenon called Prisoner Leasing. Lacking facilities to house and manage a large and growing convict population, the State allowed the “leasing” of these prisoners to various business enterprises in need of labor. It was the responsibility of the enterprise to guard, maintain and direct those prisoners it had under lease. In the antebellum South, the most valuable property a landowner had, aside from the land itself, was the slave. As chattel, they had a high value. Owners had incentive to house, feed and maintain them in as healthy a condition as economically possible so that they could deliver the labor they were intended to supply. With the advent of prisoner leasing, all this changed. Not being “owned,” but merely leased, and with a ready supply of replacements, prisoners could literally be worked to death. Records show annual mortality rates exceeding forty-five per cent.

The levees that rose to my right, huge earthen berms dug out of the heavy black bottomland, were the product of this system of labor. And as I headed for Clarksdale and the Delta Blues Museum, my plan was to visit later the source of much of that labor, the infamous Parchman Farm Prison.

The Museum

White Front Cafe

I arrived in Clarksdale (a guy named Muddy-something used to live and work around there), and followed the signs to the Delta Blues Museum. The Museum is housed on the second floor of what was once the Clarksdale Library. As you enter, on the left is the cash register and counter stacked with CDs. Along the walls are posters advertising long- past appearances of various blues performers (some legendary, some not) and in the center of the room are library stacks containing reference books on blues and blues history. I prowled around, looking at various old guitars – BB King’s Lucille, old Stellas, a National Steel, looked at pictures, thumbed through some books. I spent an hour. Signed the guest book. It was wonderful. Then I headed for Parchman Farm (a/k/a the Mississippi State Penitentiary).

“…where the Southern cross the Dog”

Tutwiler Funeral Home

On the way to Parchman I drove through Tutwiler, MS. When I saw the sign, I wheeled off the road and headed into town, looking for the railroad crossing. It was in the train station in Tutwiler that W.C. Handy first heard the real-deal blues, played by some guy with a guitar using a jack knife for a slide. It was 1903. Handy was blown away.

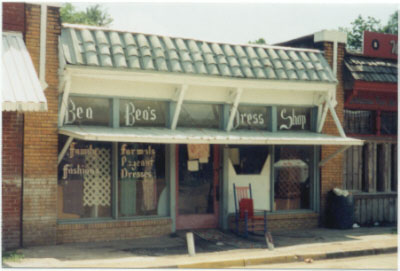

“…I’m goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog…,” the only verse Handy remembered from the tune he heard, was a reference to the intersection of the Southern Railway and the YMV (Yazoo Mississippi Valley Railroad), which was known variously as the Yellow Dog or just The Dog. Maybe I wasn’t alone in the car, but for some reason I thought of a verse Furry Lewis used in his version of John Henry, “…That Big Bend Tunnel on the YMV, gonna be the death of me” as I headed down Front Street, past The White Front Café & Joe’s Hot Tomalleys, and the Tutwiler Funeral Home (a former garage), Bea Bea’s Dress Shop straight to the crossing.

Bea Bea’s Dress Shop

No station any more. No trains either. Not for thirty years. I took a picture of the overgrown, crooked tracks, northbound, headed for Memphis,the tracks that carried Mr. Handy, his head spinning with a new sound, on up to play a date somewhere, 96 years ago.

The Shooters

Then I drove on to Parchman Farm, where Bukka White served time for manslaughter (“…sef defense,” he told me) and literally sang his way to freedom (the Governor dug it and pardoned him). There are no fences around Parchman, just twenty-thousand acres of cotton fields covering some forty-six square miles. Cotton farming there is now pretty much all mechanized. But up until about fifteen years ago, inmates worked the fields, divided into gangs of one-hundred each (The Long Line). They were guarded by six groups-of-two of their fellows, Trustee Guards, who were picked from the population because of their bad attitude, toughness and brutality. They were armed. One carried a shotgun and the other carried a 30-30 Winchester. They were called the Shooters. If someone tried to cut and run, the first shot was fired by the shotgun Shooter, aimed low, at the legs. If he missed, or the escapee kept going, the next shot came from the 30-30 and was a shoot-to-kill round. If the runner died, the Shooters were given a pardon for “meritorious service” (God’s truth…). The men in the work gang were called Gunmen (because they worked “under the gun”). Each gang had a lead man known as the Caller. He set the rhythm and pace of the work with call-and-response verses. A newspaperman who once heard this reported that the response was “…a sound that could literally knock you off your feet.”

Parchman Farm entrance

Parchman Farm

About a mile from the Parchman front gate a sign on the highway warns, “No Stopping Next Two Miles – State Prison.” Of course, I stopped at the gate, got out of the car and took pictures. I was immediately run off by two guards who told me it wasn’t such a good idea for a white boy to be taking pictures. As I approached the gate, on that mile or so of highway, I could see buildings in the distance, across a vast cotton field, low-slung and sinister, ringed by ribbon wire. These were the “camps.” There were fifteen of them and they consisted of dormitories (called The Cage) and various outbuildings, the laundry, a mechanical shop, a canning facility, etc. Through the main gate, and well into the compound, stood the Superintendent’s House (known as Front Camp), shielded from view by a copse of trees. The job of Superintendent was a patronage appointment and, very early on, it was decided that the State needed “a farmer” not a “penologist” to run the place. Parchman was to be run at a profit. And it was. In 1908, four years after it opened, it showed a profit of $800 per man, woman and child in residence (children were indeed in residence at Parchman – records show that the Black Code was blind to age, with a six- year old girl serving five years for “stealing a hat” and a ten-year old boy serving life for murder). By 1917, Parchman Farm was the single largest revenue source for the State of Mississippi. It was big business.

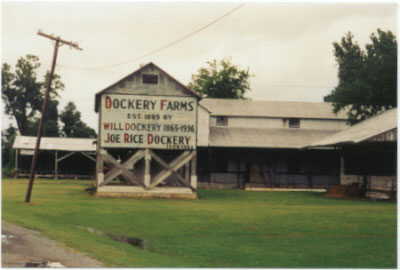

Dockery Farms

But no longer. Parchman’s acreage is now leased to farmers and cultivation is completely mechanized. Prisoner’s no longer “work the long line” and are largely confined to barracks in the “camps” spread through the institution. The sight of the Shooters and the call-and-response rhythm of the Caller are no more. I drove quickly on and swung west on Highway 8.

Dockery, Rosedale & Stovall

Next, the Dockery Plantation, and then on to the Stovall Plantation (these two produced well over eighty per cent of anybody who is anybody in Delta Blues). I passed Dockery first and found the famous sign, painted on the side of a barn, announcing to the world that Will and Joe Rice Dockery once owned the place.More cotton, thousands of acres. Muddy Waters and Charlie Patton both drove tractors on this plantation. It was a virtual hothouse for seminal Delta Blues.

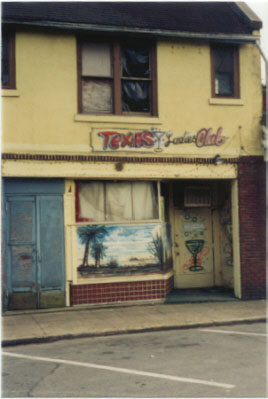

Texas Ladies Juke

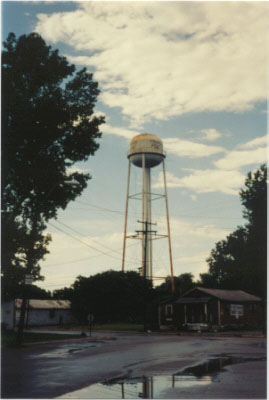

Rosedale Water Tower

Leaving Dockery, headed for the river and Rosedale (fabled in Robert Johnson lyrics), the skies began to darken. Rosedale was quite, small and green. Kudzo crept up the water tower that stood across the street from the shuttered Texas Ladies Juke.

The old Town Hall stood on the corner, its windows broken, obviously empty. I tried to imagine what it was like in the 30’s when Johnson went “…to Rosedale with my rider by my side…,” the hot Delta nights where he “barrel-housed on the riverside.” Maybe he played in some forerunner of the old Texas Ladies Juke. Maybe not. I stood in the middle of the street. A lone white guy with a camera in his hand. Looking for ghosts.

Stovall Store

I headed up Highway 1 to Stovall and Friars Point.

About ten miles from Stovall, just past Gunnison, MS, the sky opened and rain came down in sheets. I slowed from fifty down to forty, then to thirty and finally pulled over to the side, unable to see. I sat for fifteen minutes, listening to pounding Delta rain pour on to the roof of the rented Buick. Finally, it eased and I pulled back on the highway. Fifteen minutes later, a sign said Stovall, MS; a gas station/store next to a cotton gin. An arrow pointed down a dirt road, over it read “Stovall Farms.”

The Stovall Plantation, like the Dockery, was home to some of the Delta’s greatest performers. I wanted to know what living conditions were like, what the place “felt” like. Where they lived, where they worked. I didn’t know what I wanted.

Stovall Cotton Gin

All I could find was a Manager’s office and the crisp signage indicative of a big, corporate, agricultural enterprise. No “choppin’ cotton” here. Just big machinery and mechanized farming – and no ghosts. I headed for Friars Point.

Friars Point

Rolling into Friars Point, I found a truly pretty little town. It was the place where Joe Willie Wilkins and Houston Stackhouse, MBC members, used to occasionally hang when they were playing the King Biscuit Blues Show with Sonny Boy Williamson in Helena, Arkansas, across the river. The town itself nestles against the levee on the west and the Stovall Plantation to the south. Its streets wind, mirroring the bending river a half mile to the west. Main Street ends at the levee itself.

Friars Point Water Tower

Defying a sign prohibiting any motor traffic on the levee, I drove up and parked ont the top. Facing the river, to my right and left, the levee stretched on and on. Broad as a city street. I was standing about thirty feet above the town that lay at my back.

Standing there, I got a sense of the tremendous size of the thing and thought of all the effort that went into its original construction. And it was all done by hand. I turned from the river and looked back into the town. I thought of Joe Willie and Stackhouse and our days on the road together. I could see them as young men, strolling down Main Street in Friars Point, guitars in their hands. Women giving them shy looks. More ghosts.

Then back west, to 61 and up to Memphis.

Bessie

About sixteen miles out of Friars Point, heading toward Highway 61, I came to a stop sign. The road sign above it read Old Highway 61. Across the road was a sign for the “Corp. Limit” of Coahoma, MS. It dawned on me where I was. I made a right turn and pulled the Buick over to the shoulder about a mile and a half down where the road takes a sharp bend to the right, then to the left and straightens as it heads south toward Clarksdale. There was no sign marking the spot, but I knew exactly where I was – it was the spot where Bessie Smith’s car went off the road. She was heading for Clarksdale. She finally made it – and died in the Colored Hospital (now a rooming house). The story about how she died because the White Folks hospital wouldn’t take her is completely untrue. The first vehicle on the scene was the Colored ambulance and she was so far gone at that point that nothing could have saved her.

I retraced and then continued west, turning on Highway 61, north to Memphis.

That’s – 30 –

Hwy 61 Coahoma, Miss.

The rains had stopped. Across a cotton field, on my right, hung a rainbow. It raised up out of the cotton, on the far horizon, and disappeared half way up its arc into the scudding clouds. I had one picture left in the camera. I pulled off the road and walked out into the cotton. The air was damp and heavy, full of the smell of rich loam. I stood there a full minute – just breathing.

The rainbow was fading as I framed the shot. I pushed the button. The shutter clicked and the camera issued a low hum as the film rewound. And then it was quiet. I stood there a while longer. Just me and the cotton… and a few ghosts.